Structural integrity in subtractive manufacturing relies heavily on maintaining an adequate material cross-section. While high-performance applications demand aggressive strength-to-weight ratios, reducing mass without considering machining physics often invites failure. Thin features lack the static stiffness required to resist lateral cutter loads; under significant tool pressure, unsupported walls succumb to deflection or harmonic vibration (chatter), compromising dimensional accuracy.

Optimizing geometry is not merely an aesthetic choice—it is an engineering necessity to prevent plastic deformation and ensure the workpiece holds tolerance throughout the production cycle. This article explores the principles of optimal wall thickness design for CNC parts, considering how thickness directly affects structural effectiveness and ease of manufacturing. Whether you are an experienced engineer or a novice designer, the following methodologies will help you design parts that are both functional and cost-effective.

The Importance of Wall Thickness Optimization in CNC Machining

Optimizing wall thickness is a fundamental aspect of Design for Manufacturing (DFM) in CNC machining, directly influencing structural integrity, process stability, and production economics. Because subtractive manufacturing relies on workpiece rigidity to resist cutting forces, walls below critical thresholds—typically 0.8 mm for metals and 1.5 mm for plastics—often induce chatter, tool deflection, and workpiece deformation, leading to surface finish defects and dimensional inaccuracies. Conversely, excessive wall thickness increases material volume and extends machining cycle times, driving up costs without proportional performance gains. Ultimately, the optimal design must balance material-specific properties, such as flexural modulus, against the necessary stiffness required to withstand both machining loads and end-use application stresses.

Industry Standards and Design Guidelines for CNC Wall Thickness

Adhering to established wall thickness guidelines is critical for maintaining dimensional accuracy and structural stability in CNC machined components. While specific thresholds are dictated by material stiffness and functional loads, industry standards typically recommend a minimum range of 0.8 mm to 1.5 mm for metals and 1.0 mm to 3.0 mm for plastics to effectively counteract tool deflection and chatter. To further optimize manufacturability, designs should prioritize uniform wall sections to mitigate residual stress and thermal distortion, employing ribs or fillets to reinforce unavoidable thin features. Validating these geometries through simulation and early Design for Manufacturing (DFM) collaboration ensures that tolerance requirements align with specific equipment capabilities.

Strategic Wall Thickness Optimization: Balancing Structural Mechanics with Manufacturability

Defining optimal wall thickness requires a convergent analysis of geometric topology, operational stress vectors, and subtractive manufacturing constraints. While functional specifications—such as resisting cyclic fatigue or multi-axial loads—establish baseline material requirements, the physical limitations of the CNC process often dictate the final design parameters. Engineers must ensure that selected dimensions possess sufficient rigidity to counteract tool deflection, chatter, and thermal distortion, particularly when machining materials with varying hardness profiles. By integrating Finite Element Analysis (FEA) to simulate both service conditions and workholding stability, designers can precisely balance lightweight efficiency with the structural integrity necessary for precision fabrication.

Material-Specific Wall Thickness Guidelines for CNC Machining

Material selection is the primary determinant for achievable wall thickness in CNC machining, as the workpiece must possess sufficient rigidity to withstand subtractive cutting forces without deflecting or deforming. For thermoplastics, a minimum baseline of 0.030 inches (0.76 mm) is typically recommended to prevent warping, though softer polymers often require increased section thickness and conservative cutting parameters to counteract material flexibility and heat buildup. In contrast, metal components are governed by the interplay between material hardness and vibration resistance; while aluminum alloys can maintain stability with walls ranging from 0.8 mm to 1.5 mm, tougher materials like steel often necessitate thicknesses between 1.5 mm and 2.5 mm to effectively dampen chatter under heavy tool loads. Across all material categories, maintaining uniform wall thickness is critical for mitigating residual stress and anisotropic thermal contraction, ensuring consistent dimensional fidelity.

| Material | Characteristics & Considerations |

|---|---|

|

Aluminum

|

Aluminum is freely machinable and lightweight, allowing for thinner walls compared to many other materials. Care must be taken during machining to prevent deformation, especially with large or complex parts. |

|

Steel

|

Renowned for its strength and longevity, steel allows for thin walls; however, this rigidity can cause rapid tool wear. Unique cutting speeds and techniques are required, especially for specific steel grades. |

|

Titanium

|

Extremely tough and corrosion-resistant, but difficult to machine due to low thermal conductivity. Thicker walls are generally required to minimize part deformation and manage heat dissipation during production. |

|

Copper & Brass

|

These materials exhibit good machinability but their high ductility poses risks for very thin walls. They are prone to deformation, making them less suitable for extremely precise, thin-walled applications. |

Advanced Strategies for Optimizing Wall Thickness and Manufacturability

,清晰展示其-768x432.jpg)

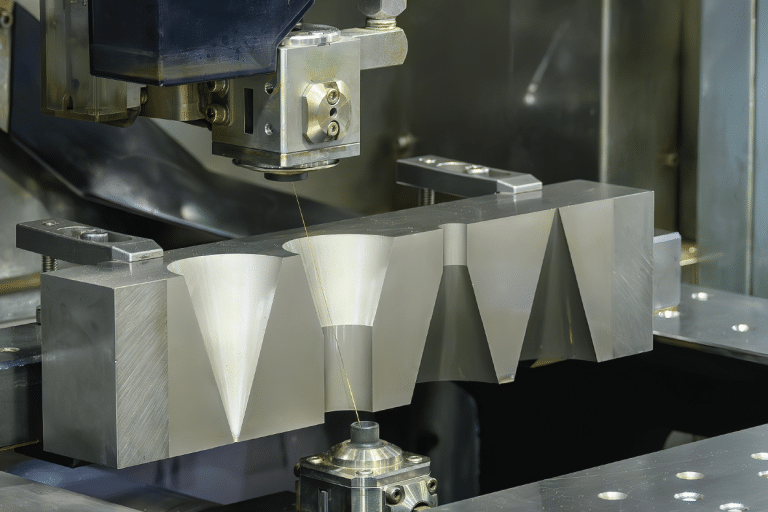

Advanced optimization of wall thickness requires a synergistic approach combining lightweighting design principles with specialized CNC execution to maximize strength-to-weight ratios without compromising durability. Engineers frequently employ geometric stiffeners, such as ribs and curvature, within high-performance alloys, validating these features through Finite Element Analysis (FEA) to identify non-load-bearing areas suitable for material reduction. However, manufacturing these thin-walled sections demands rigorous control over cutting forces to prevent chatter and deflection; this involves the use of high-rigidity tooling, reduced radial and axial depths of cut, and climb milling strategies to manage tool engagement. Furthermore, mitigating vibration often necessitates custom workholding solutions and incremental material removal techniques, ensuring that residual stress and thermal expansion do not distort final component tolerances.

Reference Sources

On-Machine Ultrasonic Thickness Measurement and Compensation of Thin-Walled Parts Machining on a CNC Lathe – This study discusses methods to measure and compensate for wall thickness errors in CNC machining, providing insights into precision and recommendations.

Wall Thickness Error Prediction and Compensation in End Milling of Thin-Plate Parts – This paper focuses on predicting and compensating for wall thickness errors in thin-plate CNC machining, which is highly relevant to your topic.

Wall Thickness Variations in Single-Point Incremental Forming – This research explores wall thickness profiles in CNC machining, offering valuable data for design and manufacturing.

Shape-Adaptive CNC Milling for Complex Contours on Deformed Thin-Walled Revolution Surface Parts – This paper examines CNC milling techniques for thin-walled parts, addressing challenges like deformation and wall thickness control.

- Stainless Steel CNC Machining Services

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the recommended minimum wall thickness for CNC machined parts? While 0.8 mm to 1.0 mm serves as a general baseline for aluminum alloys, functional designs often require dimensions exceeding these minimums. Engineers must account for auxiliary forces, such as fixture clamping pressure, and secondary processes like anodizing, which can induce deformation or alter the final dimensions of minimal wall sections.

How does feature depth influence wall thickness design? Deep pockets adjacent to thin walls force the use of cutting tools with high length-to-diameter (L:D) ratios. This geometry significantly increases the risk of tool deflection and chatter. To maintain accuracy in these scenarios, the design should accommodate step-down machining strategies or incorporate larger internal radii to reduce tool stress.

How does wall stiffness in CNC machining differ from sheet metal fabrication? Unlike sheet metal components, which derive structural stiffness from bending and folding operations, CNC machined parts rely entirely on inherent material mass to maintain rigidity. Consequently, thin machined features often require the strategic addition of structural ribs to prevent flexing that would not occur in formed sheet metal.

Why do thin walls increase CNC machining costs? Achieving tight tolerances on thin features requires the operator to reduce feed rates and use precise stock allowances to prevent the workpiece from deflecting away from the cutter. these conservative machining parameters directly extend cycle times, thereby increasing the overall production cost compared to parts with more robust geometries.